Author: Pepi Nikolopoulou

In 1983, Japanese designer Issey Miyake told the New Yorker that he aspired to “move forward, to break the mould”. His designs defied boundaries and not only broke the mould, but reshaped clothing altogether. With a unique blend of poetry and practicality, his creations blur the lines between tradition, modern technology and everyday function.

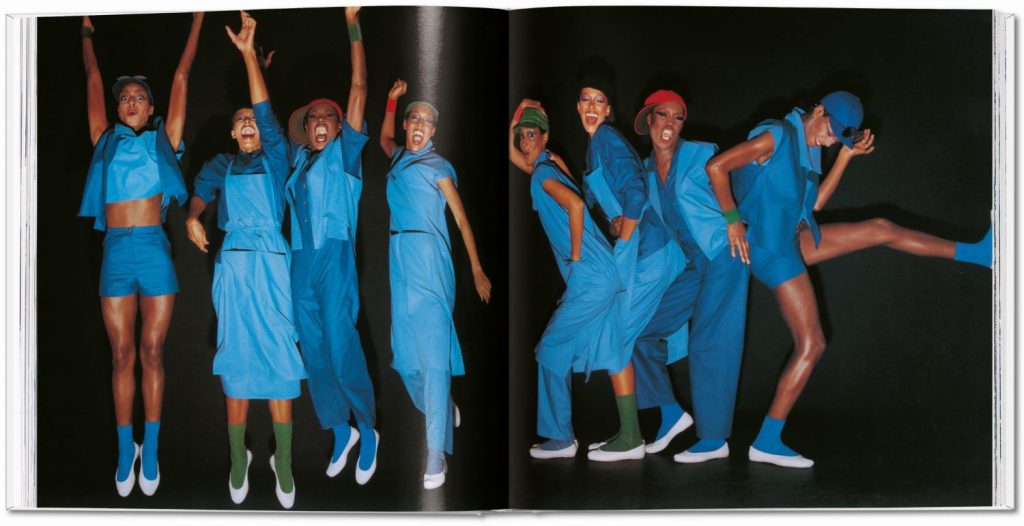

His insistence that clothing was a form of design was considered groundbreaking in the early years of his career and in time he conquered all the peaks. His designs appeared everywhere from morning to night, from factory uniforms – he designed a uniform for workers at Japanese electronics giant Sony – to grand galas and formal dances.

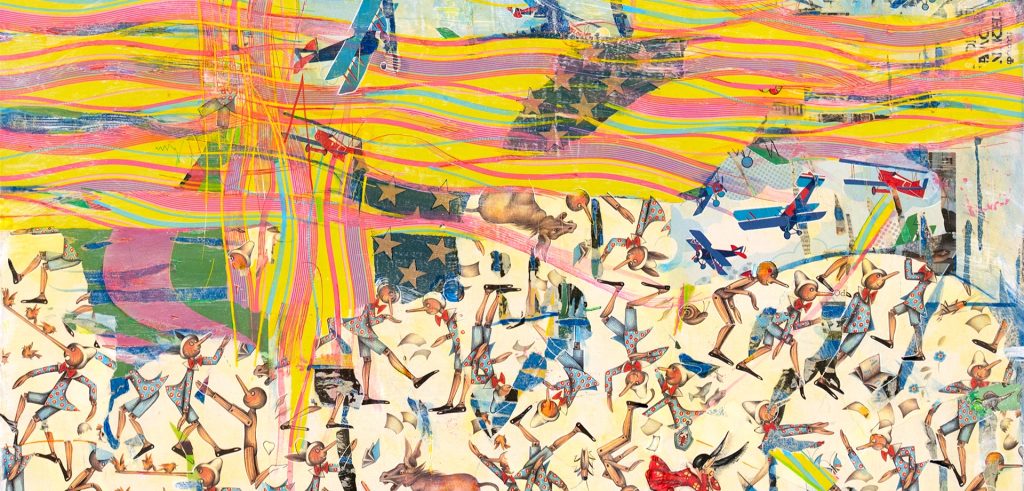

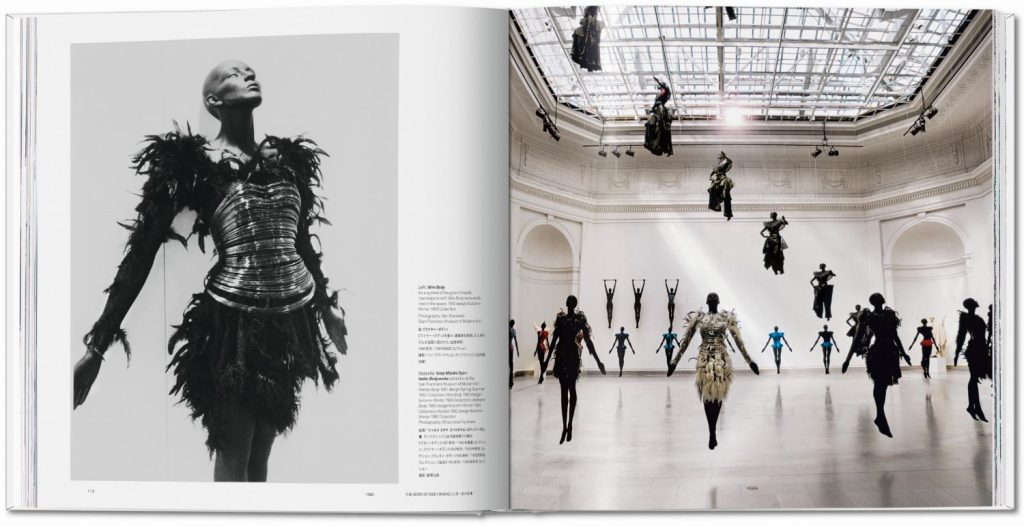

He collaborated with great photographers and architects, and his designs were featured on the cover of Artforum in 1982 – a first for a fashion designer at the time – and in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

A timeless tribute to one of the most innovative designers of our time

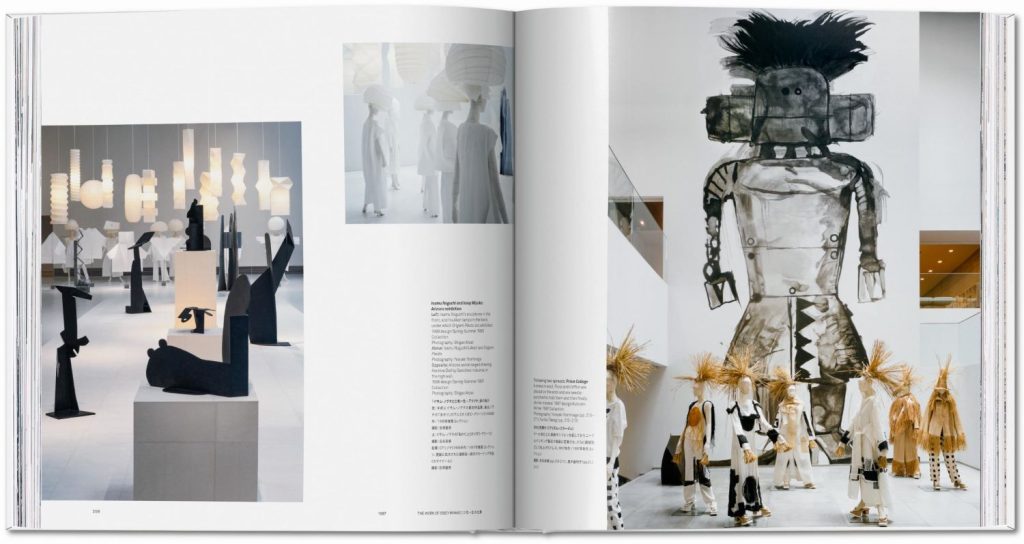

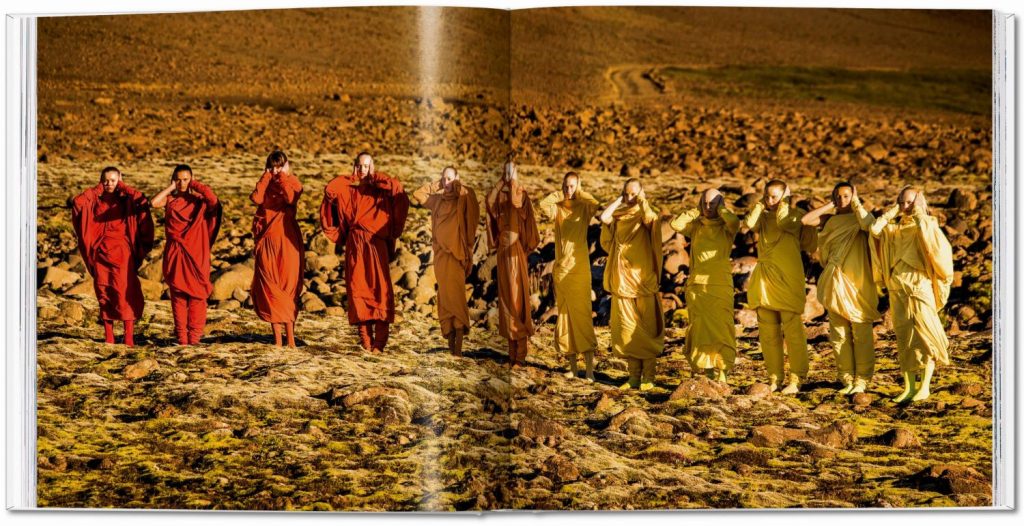

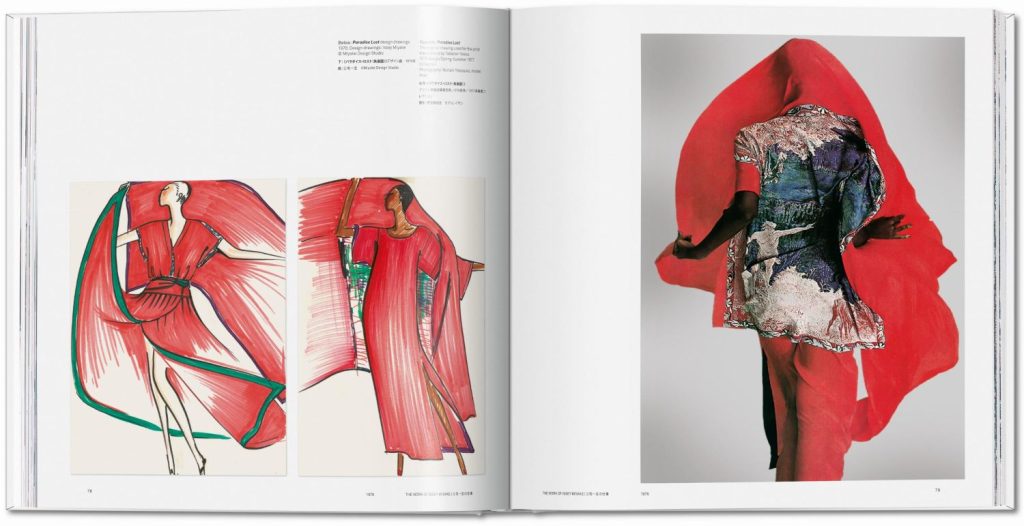

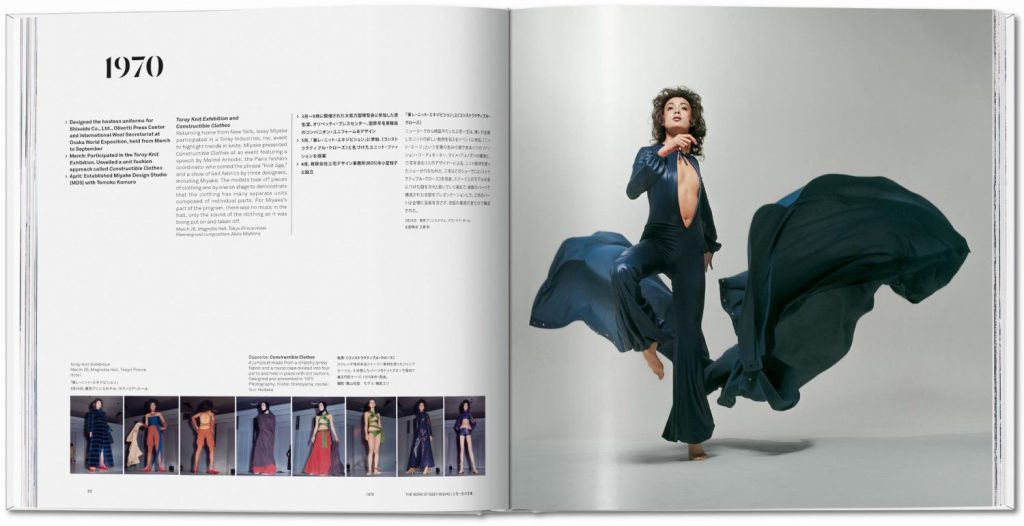

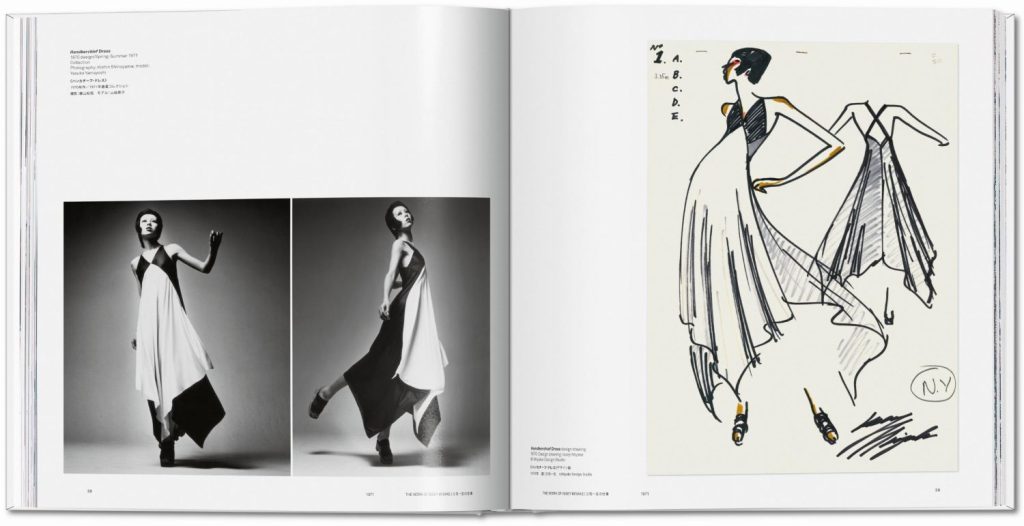

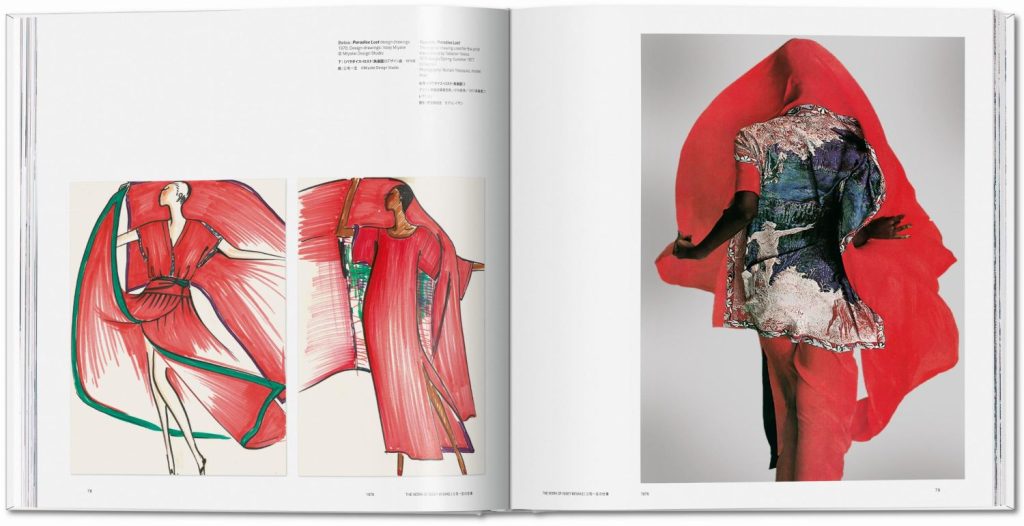

The history of Miyake’s clothes and his innovative contributions to fashion over the past decades, from 1960 to 2022, is presented in a new book entitled Issey Miyake, offering expert insight into the designer’s vision and boldness. Initiated and conceived by Midori Kitamura, the book examines the originality of Miyake’s texture-driven materials and techniques from the very early days of his career, before he even established the Miyake Design Studio.

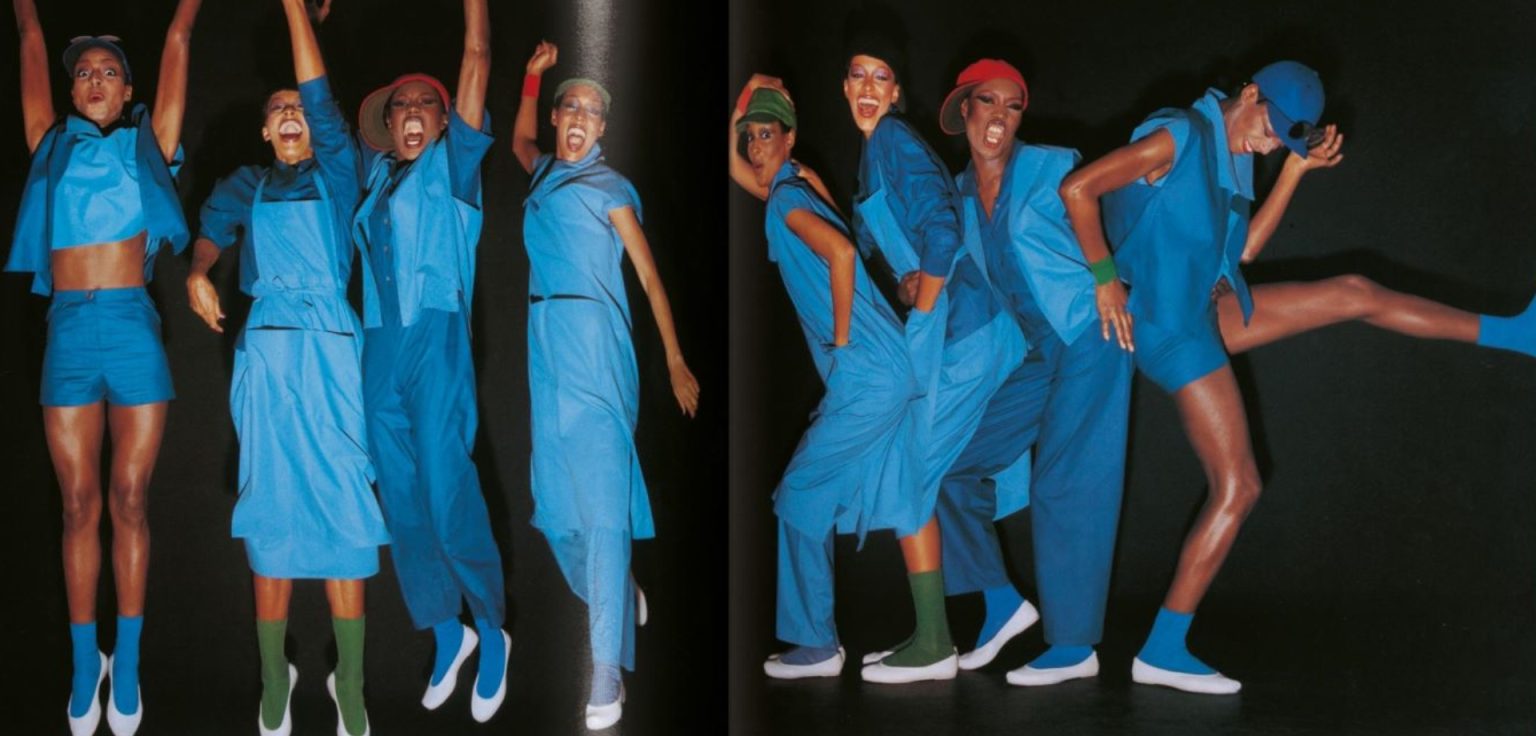

Drawing on nearly 50 years of working with Miyake, Kitamura creates an encyclopedic account of his material and technical innovations through garments based on the A Piece of Cloth concept, the 1980s Body Series, the Miyake Pleats series, and practical, everyday designs such as Pleats Please pieces.

Stunning photographs by Irving Penn, Yuriko Takagi and many others capture his clothes celebrating their special everyday originality. In her extensive essay, Kazuko Koike offers both a comprehensive chronology of Miyake’s work and an unprecedented personal profile, examining the ambitions and inspirations behind his designs from his still tender teenage years.

An innovative and daring visionary of contemporary fashion

Issey Miyake, born Kazunaru Miyake in Hiroshima on April 22, 1938 (Kazunaru in the Japanese script also reads as Issey, meaning one life). His father was an army officer and his mother was a teacher. At the age of seven, a traumatic event would stand as the defining event for the rest of their lives. At 8:15 on the morning of August 6, 1945, he was in elementary school when he saw the flash of the atomic bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. Seven-year-old Miyake set out alone for the family home, 2.3 kilometers from the center of the blast, searching among the piled-up dead and dying for his mother.

She had survived, badly burned, but died three years later after he treated her for osteomyelitis, the disease contracted from radiation. Miyake rarely discussed that day – or other aspects of his personal history – “preferring to think about things that can be created, not destroyed, and that bring beauty and joy,” he said in a 2009 New York Times article. That article was one of his rare public statements, in which he recounted how much that day and the subsequent death of his mother affected his creativity. “I didn’t want to be labelled as the designer who survived the atomic bomb.”

What sustained Miyake growing up in a poor, slowly rebuilding city was painting – too poor to buy brushes, he worked with his fingers.

The pictures in his sister’s fashion magazines would catch his attention and clothes would fascinate him from a very early age. At that time, in the 1950s, similar studies did not exist in Japan and so he would begin to take graphic design courses at Tama Art University in Tokyo. Following his passion for design and tailoring he would find himself in Paris in 1965 attending classes at the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture and then working alongside Guy Laroche and Hubert de Givenchy to complete his internship.

The student protests of 1968, against the high bourgeoisie, clients of high fashion will find him on their side. Miyake dreams of creating functional clothes, for ordinary people, without restrictions of age, size, gender or fit.

He is interested in the relationship between the body and the material that wraps it, he is interested in the feel, comfort and functionality, the softness of the fabric that harkens back to the ancient principles of Japanese clothing.

Miyake will be in New York in 1969 as an assistant to Geoffrey Beene, so that he can learn the secrets of mass production alongside him. A health crisis resulting from the radiation he had absorbed would force him to return to his home country in 1970 for treatment. Despite this difficult time, friends who believed in him and his vision would stand by him, lend him money and the Miyake Design Studio would begin operations.

He often stressed that he did not consider himself a “fashion designer”. “Anything that is ‘in fashion’ goes out of fashion very quickly,” he told Paris voice magazine in 1998. “I don’t make fashion. I make clothes.”

Mikyake appropriated technology and made it his ally in order to meet the demands of mass-produced fashion by doing away with the basic rules of tailoring that had been in place until then. His concept of One Piece of Cloth in the late 90s (later known as A-POC), pioneering and innovative, captures his design audacity. It was the idea of making clothes from a single piece of single fabric, without many seams, reducing waste and showing exactly what could be done with a knitting machine, a computer and the right know-how.

In an interview with the Japanese newspaper The Yomiuri Shimbun in 2015, he said: “What I wanted to make was not clothes just for people with money. It was designs like jeans and T-shirts, familiar to many people, easy to wash and easy to wear.”

Miyake approached craft skills and developing chemistry and technology with equal curiosity – Bao Bao’s polyester bags are plates on mesh, tough but flexible like samurai armour. He was one of the first to adopt digital design for large-scale manufacturing.

Above all, he had an unusual respect for fossil fuel-derived materials, seeing plastic, nylon and all polymers not as cheap substitutes for disposable natural substances, but as having unique properties themselves – the polyfibers he developed could be put in the washing machine, were non-shattering, elastic and skin-friendly.

An apotheosis of minimalism and utility, his turtlenecks were given a new lease of life and were adored by Steve Jobs who, along with Jobs’ Levi’s 501 and New Balance 991, became the uniform of Silicon Valley in the late 1990s, based on the idea that busy people’s minds surely have more important things to do than pick ties.

His most successful concept, Pleats Please, owes its pleated, tree-like aesthetic to ancient Greek linen garments, as imitated by Mariano Fortuny’s 1910 draped dresses, and its relatively affordable price.

Many of his designs are in museums, including the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art. In 2010, he received the Order of Arts and Letters and in 2016 he was decorated as Commandeur de l’Ordre National de la Légion d’honneur.