By professional spectator, Georgia Kotretsos

“What inspires individuals to undertake a 74-kilometer journey on foot in the name of art?”.

The profound distance traversed signifies not only the sheer commitment and determination of the audience but also their quest for authentic encounters that truly matter. In an era marked by a saturation of encounters with the unfamiliar – be it the unknown, the stranger, the foreigner, the tribal, the indigenous, the marginal, the queer, and beyond – it becomes imperative to consider the recipients of our outreach efforts.When the underrepresented are lumped together under a single conceptual umbrella, it often results in a contrived amalgamation of outsiders once again sub-categorized within the heart of the already established canon. Who then represents the insiders, lending a voice to those traditionally excluded?

Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere curated by Adriano Pedrosa, while inclusive by exclusion, neglects to bridge gaps or foster amicable relationships between opposing factions. While it sheds light on well-known issues, it neglects to address why it stands as a pertinent curatorial decision amidst over 30 geographical regions around the world currently embroiled in turmoil and conflict.

Artists themselves braved charged territories to participate, but what significance lies in presenting predominantly outsiders as novelties? The Israeli and Russian Pavilions remained shuttered, the latter devoid of the carabinieri presence seen in the previous Biennale. Are national pavilions mere cultural commodities to be bartered, shared, or rented out, as evidenced by Bolivia’s participation at the Russian Pavilion?

Standing with Belgrade-based curator Maja Ćirić outside the central pavilion at Giardini, we were prompted to reflect on the seminal “Les Magiciens de la Terre” exhibition of 1989. Have we forgotten this pivotal moment in cross-cultural history as we stand amidst emblematic indigenous work on the facade of the central Pavilion by the Makhu collective from Brazil? To pose inquiries and raise questions, one must first cover the distance, even when faced with creative expressions that prove disappointing. Yet, amidst these reflections, it is crucial to recognize that mega-shows like the Venice Biennale set the tone and trends for thematic and geographic explorations, yet when treated within the milieu of ethnography we remain mere observers of a vast cultural swamp.

Luca di Blasi’s insightful book “Der weiße Mann: Ein Anti-Manifest” (2014) reverberated in my mind as a male Caucasian artist confided his ambiguous role within the art world – that of having no fixed place, relevance, or practice to retreat to amidst broader discussions. Di Blasi’s elucidation of this predicament challenges us to move beyond self-pity and self-aggrandizement. This discourse, integral to the current Biennale, warrants further attention.

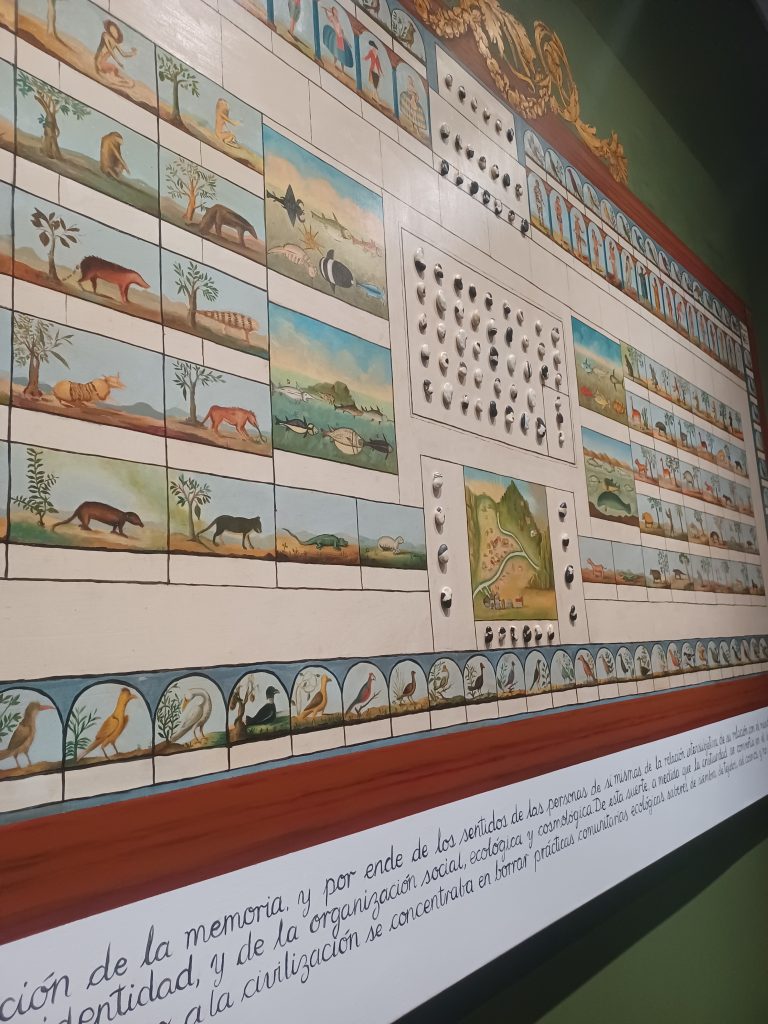

Hold that thought, as we ascend to greater heights. Beginning at Giardini, the Spanish Pavilion’s Pinacoteca Migrante, by Peruvian artist Sandra Gamarra, sets a tone steeped in colonial vernacular, raising questions about classification, documentation, and visualization methodologies. But, can we ever craft a new narrative or rewrite familiar endings using the same lexicon?

On the other hand, the American Pavilion, stands flawless by artist, Jeffrey Gibson of Cherokee and Chactaw, as it presents articulate works that transcend conventional norms in an indigenous setting-like munificent gesture. The German Pavilion, curated by Çağla Ilk, offers a meticulously curated experience befitting a mega-show – by highly instrumentalizing its mechanics.

The British Pavilion boasts an exceptional installation, albeit with an overwhelming number of videos one is called to devote uncanny attention. The Dutch Pavilion’s The International Celebration of Blasphemy and the Sacred, curated by Hicham Khalidi and initiated by artist, Renzo Martens is featuring stunning clay sculptures from the Congo-based collective Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise (CATPC) which were later cast in palm oil and cocoa in Amsterdam.

Unfortunately in the given context, it missed the opportunity to prominently feature the names of the 27 Congolese artists with vinyl lettering on its entrance alongside the curator’s and initiator’s. Here are the names behind CATPC: Djonga Bismar, Alphonse Bukumba, Irène Kanga, Muyaka Kapasa, Matthieu Kasiama, Jean Kawata, Huguette Kilembi, Mbuku Kimpala, Athanas Kindendi, Anti Leba, Charles Leba, Philomène Lembusa, Richard Leta, Jérémie Mabiala, Plamedi Makongote, Blaise Mandefu, Daniel Manenga, Mira Meya, Emery Muhamba, Tantine Mukundu, Olele Mulela, Daniel Muvunzi, Alvers Tamasala, Ced’art Tamasala. CATPC is presided by René Ngongo.

On a brighter note, the lyrical Egyptian Pavilion, “Drama 1882” by Wael Shawky, meticulously delves into imperial history through rigorous research. A refreshing multifaceted master at work. Also, Abdullah Al Saadi’s Sites of Memory, Sites of Amnesia at the United Arab Emirates Pavilion offers explorative narratives of true-telling and fiction.

Matthew Attard’s I WILL FOLLOW THE SHIP at the Malta Pavilion challenges viewers to contemplate subjectivity and objectivity having as its point of departure engravings of ships found in churches in Malta. Archie Moore’s Kith and Kin at the Australian Pavilion serves as a grand gesture, celebrating ancestry and humanity across 65,000 years.

Yinka Sonibare’s clay Monument to the Restitution of the Mind and Soul at the Nigerian Pavilion sparks critical dialogue about colonial legacies and cultural reconciliation through the lens of historical artifacts looted during the Benin Expedition of 1897. And last make time for William Kentridge’s Self-portrait as a Coffee-pot, curated by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, which offers an allegorical exploration of contemporary phenomenological inquiries.

Be sure to pick up catalogs and booklets from various pavilions to delve deeper into these thought-provoking exhibits.

Recommendations: 1. Self-portrait as a coffee-pot by William Kentridge; 2. Seeing forest by Robert Zhao Renhui (Singapore Pavilion); Courtyard of Attachments by Trevor Yeung (Hong Kong Pavilion); Field Guide to the Desert, by Mark Dion; Archie Moore’s kith and kin, and Matthew Attard’s I WILL FOLLOW THE SHEEP foldouts; and lastly, Art or Earth? The International Celebration of Blasphemy and the Sacred written by Hicham Khalidi with CATPC, Amanda Sarroff, and Renzo Martens (Dutch Pavilion).

3000 calories-burnt later, as a testament to the theme of Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere embodying my perpetual status as an outsider and foreigner to all, I urge against seeking me out for public proclamation—a lesson gleaned from the profound experiences of the 60th Venice Biennale. Hence, one only traverses the distance in pursuit of meaningful engagement with art and encounters with spectators craving engaging dialogues.